After a surgery to remove an arteriovenous malformation (AVM) in her spine, Robin Wilson-Beattie has lived with a spinal cord injury causing partial paralysis and an auditory processing disorder. Since then, Wilson-Beattie has learned that being a Black woman with disabilities means she has to self advocate to receive the care that is best for her, especially when some still cling to racial and ableist stereotypes.

Yet, she hopes to inspire others to speak up about their health.

“You are the expert on you. You may not know how it all works,” the 42-year-old diversity and inclusion educator in the San Francisco Bay Area told TODAY. “Because this is your body, you have a right to be involved in your health care decisions.”

From surgery to advocacy

More than 15 years ago, Wilson-Beattie’s doctors noticed the AVM nestled in her spinal cord. It had to be removed: If left untreated it could “explode” and be fatal. Yet, taking it out caused risks. Doctors had to cut into her spinal cord and “flay” it to remove the abnormal growth and doctors presented her with bleak possibilities.

“I wasn’t expected to walk again. I wasn’t expected to be able to use the bathroom in a typical way,” she explained. Now, "I do those things," she said.

On top of it, she was six weeks pregnant. Doctors urged her to undergo a medical termination. But that simply wasn’t what she wanted.

“There were a lot of unknowns about the surgery. I understand why they advocated for it,” she said. “With the pregnancy, they really had a whole bunch of dire predictions and those did not happen.”

But she faced a lot of judgment from her doctors. Still, she refused to end her pregnancy.

“I am really glad that I pushed hard. Even up to the day before the surgery they were pressuring me to terminate and now my kid is 15,” she said. “But out of that, I learned the power of self-advocacy.”

While recovering, she recalls an interaction with a doctor that seemed typical of how people thought of her as disabled, pregnant Black woman.

“He looks at me with just a disgusted disgusted look on his face. Not with a genuine question. ‘Why didn’t you use birth control if you knew you were going to be like that?’ and he waved at my body,” she said. “It’s as fresh as day that person’s attitude toward me and not respecting my decisions.”

Stereotypes sometimes influence the care Wilson-Beattie receives. Take pain. Some doctors don’t believe Black women experience pain like others. So some doubt Wilson-Beattie when she says she’s in pain. She recalls a doctor at a spinal cord pain clinic who wouldn’t prescribe something to relax her during a nerve ablation, a procedure where nerve is heated to stop it from sending pain signals. According to the Cleveland Clinic it’s routine for doctors to numb the area and provide a relaxing medication prior. Yet, the doctor she saw refused this.

“He didn’t listen to my lived experience with this condition, with these procedures. I know what is going on. I had this before,” she said. “He still dismissed me and ignored me and dismissed the nature of my pain.”

While Wilson-Beattie faced racist and ableist thoughts and attitudes in health care, she now has culturally competent providers and encourages people to advocate for themselves if something feels wrong. Finding a good doctor requires some research, but one's health is worth it.

“They are genuinely hearing what I have to say. They listen and we have a conversation,” she said. “All of the medical providers that I work with treat it like a partnership.”

Also, she encourages people to question people if something doesn’t feel right.

“I don’t go in there with this reverence that has been traditional in patient-doctor relationships. I treat it like any other service that I am hiring for,” she said. “We are partners going in there to make something better or maintain my health.”

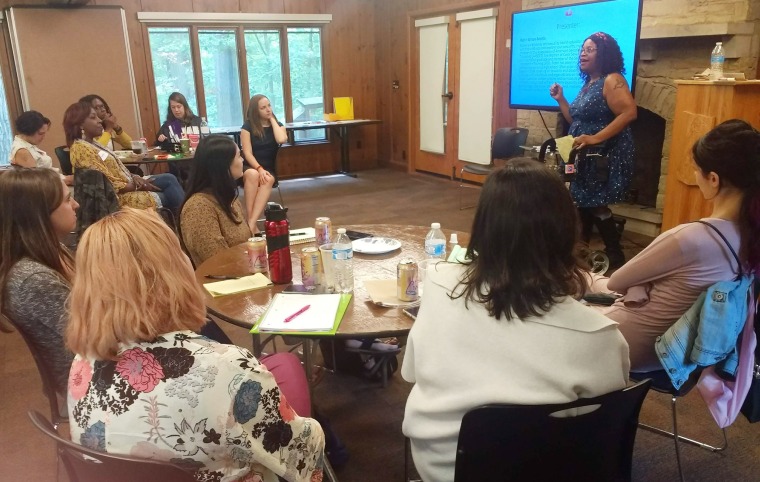

Patient advocates can educate medical professionals and Wilson-Beattie has spoken to medical students and other professionals about her experiences so they understand cultural and ableist biases. She finds that students (and doctors) are stunned when she tells them not to assume disabled patients are asexual, for example.

“As a human being I have sex,” she said. “Disability is a natural part of the human experience. I need to do all the same things that humans do, eat, breathe and I have a sex drive.”

She hopes patient advocacy and education helps health care providers and others understand the people with disabilities are just people.

“I’m just as nuanced and varied as any other person,” she said.