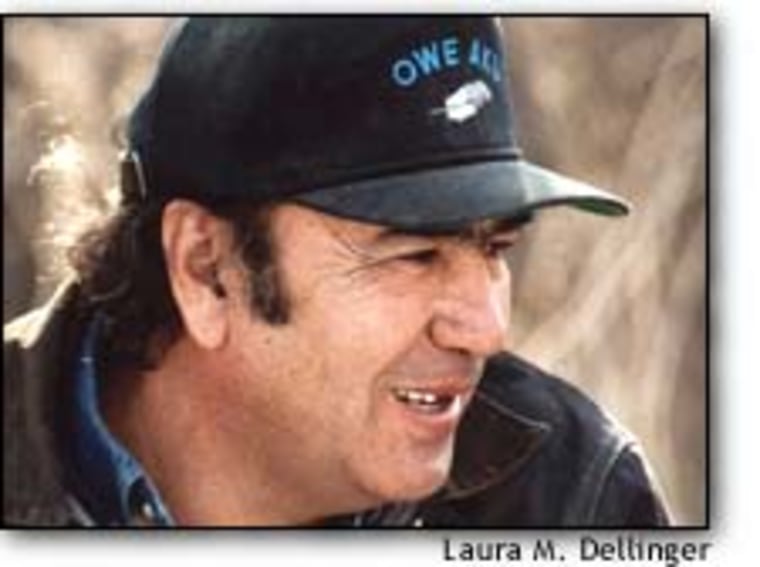

As Alex White Plume tells it, the drug raid began with the rising sun and the whir of helicopter blades. Agents from the Drug Enforcement Administration spread out across his property on South Dakota’s Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, near the Black Hills the Sioux consider sacred. “One of them came running towards me, and he pointed his gun and told me to halt,” White Plume says. “In my mind, I was going to jail.”

He wasn't headed for jail, and has not been charged with a crime, but the raid last year was heartbreaking to him. It ended what had otherwise been a charmed attempt to grow a crop that would help White Plume, an Oglala Sioux, and his family supplant their meager income from raising horses, herding buffalo and offering pony rides.

Of course, White Plume was growing hemp — the durable weed known in some forms as marijuana. All marijuana is hemp; not all hemp is marijuana, at least not in the psychotropic sense. So-called industrial hemp, which lacks pot’s chemical potency, has been used for centuries in everything from clothing to lip balm.

Marijuana usually has at least 5 percent or more of the hallucinogen tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), but industrial hemp contains less than 1 percent — far from enough to give even a mild high. And while marijuana remains illegal in most countries, the industrial hemp movement has gained momentum in recent years, especially in North America, though it’s unclear how large a market exists for hemp products.

Support from states

Canada has begun licensing industrial hemp. State legislatures in 19 states, including agricultural centers like North Dakota and Minnesota, have compiled legislation backing industrial hemp. Hawaii now allows private hemp research, and former tobacco farmers in Kentucky successfully pushed the legislature and governor to pass a bill last March creating an Industrial Hemp Commission to regulate research.

Despite pressure from states, the federal government makes little distinction between industrial hemp and the potent variety. According to DEA officials, the Controlled Substances Act of 1970 bars not only marijuana but also THC — so that all hemp, even varieties with only faint traces of the chemical, is considered illegal.

Federal authorities would not discuss the seizure on White Plume’s land. (“I can’t make any comment,” says Michelle Tapken, the U.S. Attorney for South Dakota.) Nor would the DEA discuss new regulations it says are in the works.

But when the DEA did another seizure this past July, it negotiated with White Plume in advance and came without guns pointed.

Fight for sovereignty

The seizures at Pine Ridge were largely business as usual, except for one thing: The DEA flexed its muscle on a tribal reservation. For White Plume and others in the Oglala tribe, growing these plants has become a basic issue of tribal rights. Theis tribe, they argue, has a history with hemp and a right to uphold their traditions.

“There’s a word for the plant in the tribal language, which means it’s got a history here that precedes contact with the Europeans,” says Tom Ballanco, White Plume’s attorney.

Indeed, White Plume says there is a single word — wahupta — for both hemp and marijuana. But he says he’s not interested in growing the potent variety. Instead, he hopes to turn hemp into a cash crop, selling both the finished products and seeds to others eager to harvest a plant revered in past times for its versatility and its ability to endure harsh climates and gritty soil.

It was hemp’s economic potential that drew White Plume’s attention. He was impressed by the range of hemp products, usually imported from nations such as Canada and Germany, but the high prices of hemp items stunned him.

“Most of it is import-export taxes, which drives the market up high,” White Plume says. “People in the country could pay less for a good article, and we could make some money.”

Struggle against poverty

Pine Ridge could use the help. It is often described as one of the poorest places in the nation. The town of Manderson, White Plume’s home, had a per capita income of just one-quarter of the U.S. average, according to the latest available census figures. Even the agricultural income of Shannon County, where Manderson is located, is dwarfed by most other counties in the state.

Tribal leaders acknowledge hemp could prove a valuable cash crop. They even claim to have grown it during World War II, ironically enough, as part of the federal government’s “Hemp for Victory” program.

The tribal council passed a 1998 resolution allowing industrial hemp as a viable crop on the reservation. Those who want to farm it must register with the tribal government and test their crop to ensure that it contains less than 1 percent THC.

And the tribal government eagerly supports residents like White Plume who seek to capitalize on one of the few cheap, plentiful crops that grows readily in the area’s hardscrabble ground.

“It grows wild here ... it’s growing tall out there right now,” says John Yellow Bird Steele, president of the Oglala Sioux tribe. “This is the government’s protection of corporations such as the clothing industry, the paper industry.”

Tribes and treaties

White Plume — either intentionally or inadvertently — has wandered into a legal thicket.

Tribal reservations don’t function under the same laws as the rest of the nation; though the federal government reserves the right to enforce laws against major crimes from murder to drug trafficking, tribes largely retain authority to govern themselves. Just how law enforcement is divided between the federal and tribal government depends on the treaty between that tribe and the United States.

For White Plume’s people, it was the Fort Laramie treaty of 1868. Like many treaties of the time, the Fort Laramie document actually encouraged the Oglala to take up farming as a way to end their nomadic travels across the plains. It gave each family the right to take up to 320 acres for farming, and promised free seeds and supplies.

Now that they’ve found a crop with potential to sustain them, the tribe argues, the government is hedging on the deal.

“That is the very kind of thing that the treaty was designed to encourage,” says Frank Pommersheim, an expert on tribal law at the University of South Dakota. “Here they are being thwarted trying to engage in the very sort of act the federal government was trying to encourage at that time.”

Treaties aren’t set in stone — and the government already breached the Fort Laramie treaty so prospectors could search for gold in the stark Black Hills — but unless Congress passes a specific bill to change the way the treaty is applied, tribes usually set their local regulations. They were, for example, allowed to run gambling operations almost unchecked until Congress set strict limits in 1988.

On the other hand, the Supreme Court has ruled that the illegality of some drugs — peyote, in a noted 1990 case — trumps Indian rights to sovereignty and religious freedom.

Taking a stand

While growing marijuana at White Pine would likely be illegal, the unclear interpretation of drug laws as they apply to hemp — and the treaty’s promotion of agriculture as a tribal way of life — offer White Plume and other tribal members good standing in court.

Because the tribe has endorsed hemp as a legitimate crop, federal authorities would have to clearly prove that the tribe’s right to self-rule isn’t as important as the drug laws’ application to non-potent hemp.

“You have this conflict between what the native people say the treaty means and what the United States would say the treaty means,” says Robert Porter, director of the Tribal Law and Government Center at the University of Kansas and the Seneca Nation’s first attorney general. “It sounds like a classic setup for litigation.”

White Plume is wary of going to federal court to fight a case about tribal lands. But seeing this as an issue of sovereignty — and in their minds, as another effort by the government to break its pledges — the tribe is preparing a suit of its own. Federal agencies may be following the letter of the law, but the Oglala consider this a personal assault by a government they feel has a history of betrayal.

“Even if they do win, what do they win that they beat down a tribe again?” asks Ballanco.